“It’s normal to get a little teary in there,” James Turrell reassures me as I sign a waiver before lying down on a bed that slides into a sphere that looks like a cross between an MRI scanner and a UFO. “You’re also agreeing to give me a good review when you sign that too,” jokes the American artist.

The waiver confirms that I don’t have epilepsy, a pacemaker or claustrophobia – his 2010 artwork Bindu Shards could potentially trigger any of these things. I’m in a tight, enclosed space and there are bright, pulsating lights making me lose not just my sense of depth, but any idea of whether my eyes are open or closed.

It would be easy to describe the cell as a light show, but it’s far more than that. The “real” show is happening inside my head. “It doesn’t actually change, it’s your perception that changes,” says Turrell. “This is behind-the-eye seeing. All those things you see there are not projected on that dome – there’s nothing there at all.”

Part of his Perceptual Cells series, Bindu Shards is one of the major works that make up the Turrell retrospective at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. While intense, the cell is designed to induce the state of mind that occurs in the early stages of meditation – the sort of drifting off sensation that happens when you gaze into a fireplace.

“One of things I’ve always been interested in is the theta state,” says Turrell. “That’s thinking, but not thinking in words.” The alpha state and theta state occur naturally on the path to rest and sleep, he explains, and the light and sound in the cell prompts the brainwave entrainment that makes that happen.

While all this might sound a bit bizarre, Turrell has a wealth of knowledge to back up his ideas, including a degree in perceptual psychology and another in mathematics. But though his art revolves around various scientific concepts, he does not have the same intent as a scientist. “I know that science is very interested in answers, and I’m just happy with a good question,” he says.

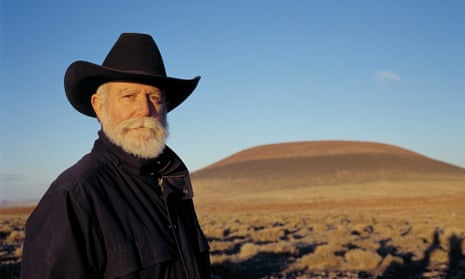

Turrell is also a trained pilot and the influence of flying can be felt in several of his works that induce a sensation of floating in space. It was while flying his plane over the Arizona desert that he spotted Roden Crater, an inactive volcano that has become the centre of his lifetime’s work. With the help of astronomers, he turned the crater into a naked-eye observatory, with tunnels connecting various other installation spaces. Still a work in progress, the crater is a much sought-after experience open only to friends and special guests of the artist.

Volcanoes aside, Turrell’s main inspiration is a lifelong fascination with light. He always wanted to deal in it, he says, but “didn’t know quite how that plugged into society or where you got a job doing that”. He was strongly informed by the way artists like JMW Turner, John Constable and Mark Rothko depict light in their paintings, and also cites dioramas and the camera obscura as influences for his experiential pieces.

Turrell’s first projection pieces in the late 1960s raised questions around the very definition of art and reactions to his work were mixed. “People said I was just shining light on the wall,” he says.

Both his obsession with light and the idea of art as an experience stem from Turrell’s Quaker upbringing. “The Quakers don’t believe in music or art, they think it’s a vanity,” he says. However, his Quaker spirituality evidently informs his work.

Turrell describes the paintings of Quaker preacher Edward Hicks as a major inspiration because of its message of peace. As a child, Turrell recalls sitting through long, meditative Quaker meetings. “I would just sit there and think about the meeting house, and I would think: wouldn’t it be terrific if it was a convertible?”

This childhood urge to peel the ceiling back birthed Turrell’s famous skyspaces – outdoor viewing chambers that alter viewers’ perceptions of the sky. Meeting was the title of his first public skyspace, which he began in 1978 at the Museum of Modern Art PS1 in New York. Since then, Turrell has made 89 around the world. Within/Without (2010), a permanent work at the National Gallery of Australia, is his 82nd. Currently, he is also working on one for the Museum of Old and New Art (Mona) in Hobart.

Each skyspace is site-specific, and Turrell visits those sites multiple times before making them. “I respond to what the sky is: you have maritime skies, desert skies, and you have high desert skies. I’m doing some also in the Alps – and there you have the really crisp blue that can happen in the winter, which is almost like a blue you can cut into cubes.”

While Canberra cops a lot of flak for its weather, it certainly puts on an impressive blue sky – in this sense, says Turrell, it’s a lot like Arizona. How we interpret colour in a skyspace depends on the context of our vision, he adds. “We think we receive all that we perceive but in fact we actually give the sky its colour. And because we give the sky its colour, as in the skyspace here, I can make the sky any colour you choose.”

Space is intimately linked to the passing of time, says Turrell, whose gallery works can take a certain amount of time to adjust to. Orca (1984) for example, needs eight minutes before the eyes begin to register the changes of light in the space.

The light in Virtuality Squared (2014) from his Ganzfeld series, is programmed to change over time. What at first appears to be a flat projection is in fact a large room that viewers enter, engulfing them in what seems like a never-ending expanse of colour. As the colour shifts, our perception compensates, and static light is suddenly not static at all.

“Each day is a different length of time and that gives a different length to the cusp between light and darkness or darkness and light,” Turrell explains. “I’m making the piece for that cusp – to be most active then.”

The cusp, or threshold, between light and darkness, and between what we believe and what we perceive – that moment when we realise something isn’t flat when we thought it was, or that it is static when we thought it was moving – are the moments Turrell manages to suspend us in, sometimes for surreally extended periods of time.

Turrell’s art reveals the multifaceted dimensions of his own life. But by pairing things back to a single element – light – his work becomes a window into a state of being beyond words. “This wonderful elixir of light is the thing that actually connects the immaterial with the material,” says the artist. “That connects the cosmic to the plain everyday existence that we try to live in.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion