By his own admission, South African artist William Kentridge’s career got off to a slow start. Even by the time he was in his mid-40s and had built a reputation in his own country, a UK broadsheet critic could declare without embarrassment that he had never heard of Kentridge when reviewing, positively, his 1999 show at London’s Serpentine gallery. It is not an admission that has been made much since. Kentridge’s work is shown and collected by great museums all over the world and his growing status as a public intellectual saw him deliver the prestigious Norton Lectures at Harvard in 2012.

Kentridge will be difficult to avoid in London this autumn. His first major UK show in 15 years opens at the Whitechapel Gallery later this month. It will be followed by his own design and direction of the English National Opera’s production of Berg’s Lulu, a collaboration with the composer Philip Miller at the Print Room, as well as a lecture.

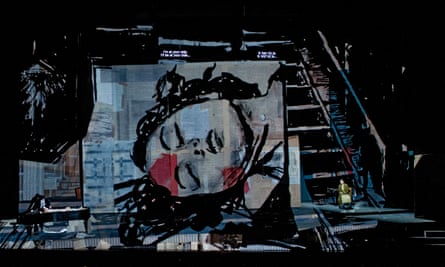

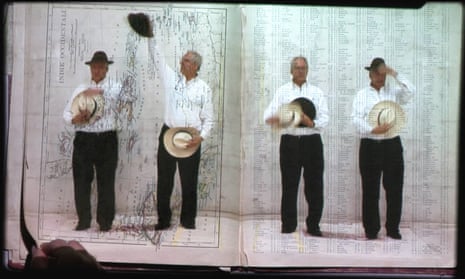

But while Kentridge and his work will be appearing in different venues and in different mediums, there is far more that connects these apparently disparate events than divides them. His production of Lulu is underpinned by his distinctive expressionist charcoal drawings and animations. The event at the Print Room involves the human voice as well as film. His lecture has a strong element of performance and includes specially made artwork.

“When I started out I tried to follow the, well-meaning and sensible, advice of all my friends who told me to do one thing and do it well,” he explains. “Just do drawing, they said. Just do theatre. Only make films because otherwise you get caught between them. For a long time I tried that, and I failed at all of them. Now I don’t even pretend to know what form an idea will ultimately take or what project it will end up in. I just get on with doing things knowing they will end up somewhere.”

Observing Kentridge at work in Johannesburg is to get a sense of the scale of his production. He has two studios, one at the family home where he was brought up in the old-money suburb of Houghton, near where Nelson Mandela spent his last years and a neighbourhood in which the primary selling point of property is now the size of its security walls. His other studio is in a larger space downtown in what has become an artistic oasis in a city centre that had been hollowed out by crime and the flight of commerce. But just as the whole of Johannesburg life seems to be present in his work, so his pieces come from all over the city. This year his gallery, the Goodman, celebrates 50 years of presenting art that has challenged black and white elites alike. Kentridge is not only its star artist, but a sponsor and supporter of other artists in a society in which state subsidy is vanishingly small. Much of his artwork is produced by David Krut’s print shop, next door to the downtown studio; Kentridge works closely with one of the last foundries in the city, and a few miles out of town is the Stephens Tapestry Studio, with whom he has been collaborating for more than two decades.

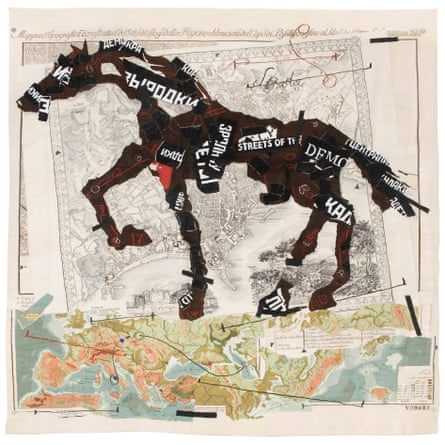

Work from all these sources will be in evidence at the Whitechapel show in the form of installations, film, sculpture, drawings, tapestry and prints, often featuring the artist himself in his habitual uniform of dark trousers, white shirt and pince-nez glasses either perched on his nose or hanging round his neck. They combine to address Kentridge’s eternal subjects of time, art, colonialism and utopian politics. The newest work – only completed in the last few weeks – will be an installation, Right into Her Arms, in which two corrugated cardboard screens are transformed into recognisably human characters who dance a sexually charged pas de deux. The piece not only exemplifies Kentridge’s enthusiasm for cross-fertilisation, but also his underlying artistic and political preoccupations.

“It is someway between Dada and a cabaret performance,” he says. “These were things I was looking at while making Lulu but they didn’t get into the final production. Our initial goal was to make programmable, movable screens to see what projected images looked like on them as they shifted. It was quite a challenge and the team had to develop new software. But soon the focus changed to whether the set itself could become the protagonist. And what began as just a way of receiving images of Lulu and her lovers, ended up with the screens being lovers themselves. I’m always interested in what I call the ‘less good idea’, by which I mean the secondary idea. You start with one plan and then something better emerges from the periphery that would have been impossible without the first thought.”

Right into Her Arms also connects to another installation in the show, O Sentimental Machine, which is about Trotsky’s declaration that human beings were semi-manufactured products. “A lot of Soviet thinkers were concerned as to what would happen to imperfect people in a perfect society. They asked if our emotions were mechanical, could we get rid of rid of rage and jealousy and so on which would make it so much easier for us to get along? You can see how well that went. But the counterpart is the very contemporary idea of can we teach machines to be human? And so in Right into Her Arms the micromovements of the screens that appear to be like human pauses and shifts and hesitations, effectively become the work.”

Scattered across the exhibits in the Whitechapel will be Kentridge’s trademark collection of shapeshifting images of objects such as the stovetop coffee pots – familiar from Picasso and Braque – that he morphs into a woman dancing, or a rocket crashing into the moon, or an elevator descending into the gold mines on which Johannesburg was built (or, sometimes, a device for making coffee). “It’s a bit like commedia dell’arte,” he says. “You have your set characters and they are sent off to perform different shows every night. The coffee pot is just standing there waiting to be used in different places. There are lots of rhinoceroses, typewriters, megaphones that keep coming back. Cézanne spoke about the world being constructed from cones, spheres, and cylinders. Which is a way of taking the world and formalising it. I like the idea of Cézanne’s cone but I wanted to send it back into the world to earn its keep which it does in the form of a megaphone. They are formally interesting, but they also bring so many associations, from mass rallies, to delivering instructions, to Nineteen Eighty-Four.”

In his attempts to codify the place of politics in his work Kentridge says he likes the example set by Manet, “who did very political work but also painted a lot of flowers. I’ve never felt I needed to distinguish strongly between work that was about the history of art and work about the history of the country. It all flows into the studio and different parts get picked up at different moments.”

Kentridge, despite being born into white privilege in Johannesburg in 1955, was exposed to the implications of the history of the country from the outset. Both of his parents were prominent liberal lawyers: his father, Sydney, acted for Nelson Mandela at the 1958 treason trial and later for Desmond Tutu and the family of anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko; his mother, Felicia, was instrumental in providing legal support to those denied it by apartheid. He says by the end of primary school he was aware that “my parents held different views to the majority of other boys’ parents who took for granted the way society was organised. And it was becoming clear to me that we were in a very unnatural society.” At university – his last year coincided with the 1976 Soweto Uprising – he produced agitprop art and posters and was involved in political theatre. But he never joined a party, saying he was “too aware of the contradictions and the ambiguities of all the statements of certainty that were the basis for political parties. I was always happier to be at the edges of things, and while my sympathies were with the ANC, I never became a member.”

After leaving university he began to draw and make prints and then studied theatre and mime in Paris. He developed a working relationship with the Handspring Puppet Company – now best known for their work on War Horse – that has continued to this day. But his early career as an artist was underwritten by work as an art director in South African TV and film industry. “It was so low-budget that I was really the person who borrowed my friends furniture. So my initial career ambition was to sell some drawings and see how long I could survive before having to go back to the film industry. And I did sell enough drawings, but let it be said, for a white South African artist there were so many safety nets. My wife was a medical doctor so she had an income. There would have been family to catch me if they hadn’t sold. It is very different for black artists, who are usually much more out on a limb. And fundamentally that is still the case.”

As a newly professional artist he says he was aware of the wider art world, and he took a very conservative view of it. “I was as sceptical and derisory as anyone at the thought of a person putting a pile of bricks in the Tate. Joseph Beuys’s idea of pumping honey through a tube around museum as political art? That wasn’t politics. Politics was the police arresting you and putting electrodes on your testicles. I was interested in early modernism, and having been brought up in a society full of violence and absurdity I understood the Dadaists very well. But I couldn’t see the link between them and the minimalists and conceptualists. It’s taken me a long time to me to appreciate it and I had to be dragged kicking and screaming into understanding the world I was in.”

He suspects such thinking was part of a postcolonial insecurity. “You have to come from the centre of the Empire to have the confidence to say that whatever rubbish I do, it will be given the benefit of the doubt because I am an American, or whatever, doing it. And that does enable very interesting work to happen.”

It wasn’t until the late 80s that Kentridge stumbled upon the idea of combining his drawing and film-making to create idiosyncratic, animations. He describes the technique as “poor man’s animation” in that he rubs out and reapplies charcoal marks to a drawing on a single sheet of paper, taking images of each change. The series of allegorical films he made in this way from 1989 to 1996 – about a property developer, his wife and her lover – made his name in South Africa. His international reputation was established when his work was shown at the 1997 documenta show in Germany. “It did feel like a breakthrough – before then I’d been more known as a theatre-maker through the work of Handspring.”

He says when he was younger there was a sense that if you wanted to be part of the international art conversation then you had to go to New York or London or Paris. “That doesn’t seem so essential now,” he says, “although it’s still important for your work to be shown there.” Surveying the global scene, he thinks London has enjoyed something of a comeback over the last decade or so, after the YBA years during which it “became almost entirely self-congratulatory. That was all there was and everyone else in the world didn’t really count. From outside Britain it was completely insufferable. It felt like a closed club, but feels much less so now.”

His parents left South Africa for London, as have his siblings and one of his three children. But he says he intends to stay despite declaring himself “cautiously pessimistic” about the country. “There are very hard things to overcome. The anger and disappointment about what has not happened in the last 25 years grows and grows. Race is becoming more prominent as a factor rather than less. What is to show for the majority of the people since the birth of the rainbow nation? There is a lot. But it is not enough. I think we’re in for difficulties in the two years ahead.” He says that he could have left, and “that in some ways it has got harder to work in that here’s no longer a laboratory that processes film, for instance. You have to send it to Europe. But there is still a print shop and a foundry that I need. There are actors and musicians, puppet makers and tapestry weavers. So much of my work – in its content and its making – is dependent on being in Johannesburg and what it offers. The very fact that after 61 years I’m still here means there is something strong holding me here.”

- William Kentridge: Thick Time is at the Whitechapel Gallery, London E1, from 21 September. Lulu opens at ENO, London WC2N, on 9 November. Paper Music is at The Print Room, London W11, from 9 October.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion