Shanghai still thrills to James Turrell’s light fantastic show

The American artist uses light and holograph technology to create meditative installations that manipulate light and space, and his first retrospective is still wowing Shanghai after three months

More than three months after James Turrell’s solo exhibition opened at the Long Museum in Shanghai, hundreds of visitors are still coughing up 200 yuan (HK$226) to see it.

“James Turrell: Immersive Light”, which runs until May 21, is billed as the Californian artist’s first comprehensive retrospective in mainland China and has divided the museum’s cavernous, industrial-inspired space up into 15 rooms, each housing an installation.

Walking into each installation, a familiar feeling descends. It’s almost like entering a holy place – a temple or church – where the air is cool and the mind settles easily into contemplation.

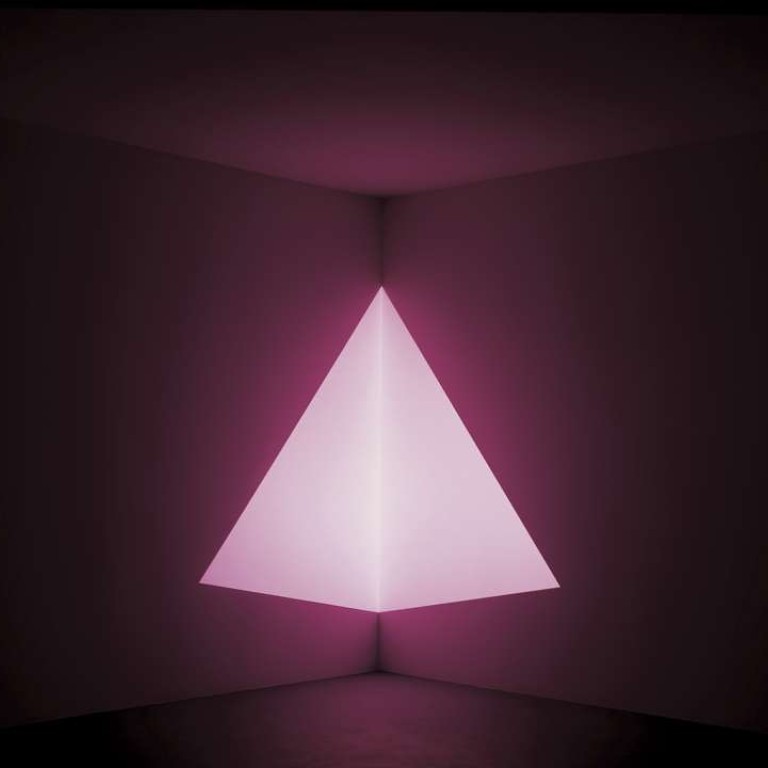

In a dark room, light projections of differing sizes and shapes can be seen on the walls, their colours – blue, green, purple and orange – gradually changing over a long period of time.

The first room of “Immersive Light” contains a 1976 piece entitled Ganzfeld, which is based on sensory deprivation experiments Turrell and his contemporaries conducted in the late 1960s.

Its design creates the illusion of indeterminate and undefined space – there are no perceivable, fixed dimensions, just a tangible light substance emanating from a wall while viewers are seated opposite, allowing the fog of light to wash over them.

Shallow Space builds upon the vocabulary of the Projection Pieces but with lights hidden and lit behind and inside a partition wall, which seems to float, the light surrounding and coming through it with a soft, glowing effect.

In more recent pieces, Turrell has also embraced new technology to create holograms. In “Transmission Light Work” (2008) the 3D object of the hologram is light itself, a multidimensional fragment of light that can be observed from different angles as you walk around the room.

The effect of each installation is meditative. When immersed in one of Turrell’s pieces, viewers become ultra-aware of their surroundings: the silence, the stillness, the temperature-controlled air, and even the sound of a furtive selfie.

This meditative feeling is even more dramatic given the setting of the exhibition in Shanghai. To step outside the Long Museum into the city’s notoriously frenetic urban pace is jarring, and re-entering the outside world of sharp lights and oppressive traffic noise takes some readjustment.

Though Turrell’s work is ostensibly about how light and space are perceived, it is also, perhaps more importantly, a conduit for examining how these perceptions can make a person feel.

The man himself is fond of saying: “My work is more about your seeing than it is about my seeing, although it is a product of my seeing.”