- India

- International

Sheba Chhachhi talks about what kept her vision alive over 40 years and why she prefers to be a ‘citizen artist’

In June, Sheba Chhachhi received the Prix Thun for Art and Ethics award.

As documentary photographer and activist, I photographed the women’s movement across the 80’s, pointing the camera one moment, shouting slogans the next: Sheba Chhachhi. (Source: Jonathan Page)

As documentary photographer and activist, I photographed the women’s movement across the 80’s, pointing the camera one moment, shouting slogans the next: Sheba Chhachhi. (Source: Jonathan Page)

In the last four decades, Sheba Chhachhi, an artist, photographer and women’s right activist, has successfully investigated questions concerning gender, ecology and urban culture. Awarded the prestigious Prix Thun for Art and Ethics award last month, her archive of images chronicle numerous issues, from dowry deaths to India’s women ascetics and the putrid Yamuna. Often, through her work she has sought an alternative perspective: If her immersive installation The Water Diviner (2008) borrowed from Indian lore, history and contemporary writings to showcase the importance of water in Indian culture, in her photo installation, When the Gun Is Raised, Dialogue Stops (2000), Chhachhi, presented the voice of the women of Kashmir, who, she noted, offered an alternative to the “dominant, hegemonic” representation of the war-torn region. The National Institute of Design alumnus speaks about representing social concerns, experimenting with material and being a Citizen Artist.

The award recognises artists who promote sustainability through their work. Much of your work is focused on the environment alongside issues of gender. If you could discuss this relationship that you have built between the two pursuits.

Ecology is a feminist issue. I see these two concerns as deeply intertwined — for me, feminism is a political philosophy, a way of thinking and being that refuses a separation or a hierarchy between the personal and the political; nature and culture; body and mind; sexuality and spirituality, human and non-human — core ecological values. It is this conceptual ground, apart from a number of equally significant material linkages, such as, for example the heavier consequences of water shortages on women’s lives, which connect, what may seem, on surface to be separate issues.

70 Synonyms for Water in Sanskrit.

70 Synonyms for Water in Sanskrit.

In much of my recent work I have tried to bring back into the conversation ideas and images from pre-modern culture, which offer ecological wisdom, to reflect on the degradation of our environment, particularly that of Delhi and the River Yamuna. This has often taken the form of large public art projects. I am interested in creating pools of intimacy within public space – to open a conversation, to create the possibility of an encounter, an exchange and shared reflection.

As an artist, your research base covers a wide spectrum, from mythology to history, literature, Chinese landscapes, miniature tradition and science. If you could please talk about the confluence.

Research is basic to my work method – I may start with an idea, or an image, and then begin to research and think around it, building a web of associations, or be held by something I read, and develop that into an artwork.

For instance, I follow new imaging technologies with great interest – from medical to satellite, and frequently visit sites such as NASA. Here I was struck by the eerie beauty of satellite images of ecological disasters. I began looking at satellite views of floods, earthquakes and droughts in South Asia, as a form of contemporary landscape. In “Edible Birds”, a triptych of animated light boxes, these landscapes form a backdrop to human figures in yoga asanas, which mimic the postures of birds, another form of relating to the non-human. Masses of edible birds – chicken, hens, and pheasants — bred for consumption scroll across these bodies. The artwork places into one frame very different, contradictory modes of relating to the earth.

Another work, “Winged Pilgrims: A Chronicle from Asia”, is a large immersive installation that weaves into moving tapestries landscape traditions and fables stretching across Asia: from Persia to Japan, with India and China as important nodes, and across time: from 6th century Buddhist texts to documentary photography. The figure of the bird is the leitmotif, and the especially composed sound track reflects this geography as well. I must have spent more than a year absorbed by the richness of metaphors that my research revealed.

In 1984, you co-founded Jagori ‘to spread feminist consciousness for the creation of a just society’. During this period you took several “activist” photographs, how do you view these with reference to the later photographic work, for instance Seven Lives in a Dream (1998), which included portraits of Urvashi Butalia (author and publisher at Zubaan) posing with typewriters, activist Shahjahan Apa surrounded by utensils at her home. If you could also discuss the journey to your first installation in the 1990s.

The difference between the photographs made in the 80’s and the staged portraits of the early 90’s is not that some are ‘activist’, and the others are not. The difference is between documentary images and staged/constructed portraits, both are of feminist activists.

The Water Diviner.

The Water Diviner.

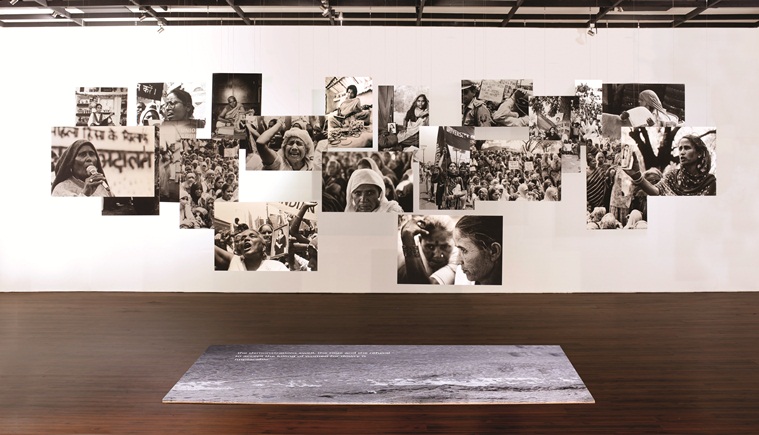

As documentary photographer and activist, I photographed the women’s movement across the 80’s, pointing the camera one moment, shouting slogans the next. After 10 years of creating images that interrogated stereotypical representations of women, I realised that my own images of militant, struggling women had simply become a new stereotype.

It became necessary to find a way of creating portraits which shifted away from the colonial recording of ‘natives’, unconsciously reproduced in post colonial documentary practice, to a representation of ‘citizens’.

In 1990, I invited seven women activists – friends, sisters, and fellow travellers – to collaborate with me in developing a series of staged portraits. Each woman chose a place, a posture and materials and objects that she felt could speak of her, tell her story. The process of developing these ‘theatres of the self’ was complex and long drawn, developed through intense, intimate interaction over several months. Seven Lives and a Dream,1990-91, includes documentary images from the 80’s of these same activists, along with the staged portraits made collaboratively in 1990/91.

By 1993 I moved to photo-based installation. I was troubled by the commodified consumption of photographs, whether in media or art space. Relocating the photograph as an object within sculptural space offered the possibility of reconfiguring the habit-ridden encounter with a photographic image. I wished to reinvest the viewing of photographs with time. I was also experimenting with sculpture, and text had always been important to my work.

These elements first came together in a series of photo based installation works titled Wild Mothers. Wild Mothers I, made in 1993, had hand tinted B&W photographic portraits of contemporary women ascetics held within yonic terracotta sculptures. These rested in an expanse of sand and pigment akin to an archaeological site, littered with broken fragments of terracotta tablets carrying the poetry and representations of women like Lalded, Akka Mahadevi, Janabai, Karaikalaamiyar etc. from the 4thC onwards.The work explored a relatively unknown territory of female experience, mined with patriarchal oppositions between sexuality and spirituality, the body and the spirit, the sacred and the profane.

Do you often turn to your own archive, not necessarily explicit in your work. Of course in the 2012 installation Record/Resist you had used photographs of Satyarani Chadha and Shahjehan Apa, whose daughters were murdered for dowry and both of whom became active in the contemporary women’s movement from the late 1970s. What prompted you to go back? In the same work, you also refer to the loss of public space. How do you look at that concern in the current times?

I often return to earlier questions, images and ideas. I believe that meanings accrete over time, and that each time one returns to an image, new depths and meanings can emerge. In 2012, I was provoked by the curator of the Gwangju Biennale to revisit the archive of the women’s movement. She was trying to understand the rise and sustainability of people’s movements in the light of recent, powerful, but short-lived uprisings such as the Arab Spring, Occupy, by looking at the histories of more sustained struggles.

Neelkanth poison nectar.

Neelkanth poison nectar.

I created a photo-video installation, Record/Resist, where the video, projected on the floor annotates excerpts from the photo-archive that are suspended in space, allowing the viewer to walk through and between the images. The video blurs boundaries between personal memoir and historical event as it investigates the meanings, slippages and contradictions within collective resistance. In one sequence, I moved images of demonstrations across India Gate, like ghosts, referring to how we used to occupy these spaces and how protest today is corralled into Jantar Mantar. I completed the work in September – uncannily, in December, India Gate was ‘occupied’ by thousands protesting against the horrific rape of Jyoti Pande.

Today, protestors address each other, rather than the people of the city at Jantar Mantar. Public space is increasingly controlled, and securitized making media the only conduit to reach larger audiences. The public sphere for political action has shrunk.

For your project Ganga’s Daughters, you spent over a decade understanding India’s women ascetics. How was it for you to bring their concerns to the fore?

My interest in women ascetics began with some early encounters while I was travelling in Bengal and other parts of rural India as a student. In the early 90’s, I read ‘Speaking of Siva’, translations of free verse lyrics written by four major saints of the 10/12th century Bhakti movement, from Kannada to English by AK Ramanujan.

I was struck by the powerful poetry of rebel, mystic and poet Akka Mahadevi. What particularly interested me was the bringing together of the erotic and the spiritual, in a culture where the two are normatively opposed, the scathing rejection of conventional female roles, the articulation of the body — self relationship – her voice was absolutely contemporary!

I was also interested in looking at indigenous, premodern forms of feminism, irritated by the constant accusation of being ‘western’ that the women’s movement faced. Deeply affected by Akka’s couplets, I began researching women ascetics from ancient and medieval India. Although there was very little sociological work at the time, I found a rich repository of poetry, stories, images and hagiographies from the 6th century onwards. Some of these texts were retrieved by feminist scholars, as part of the project ‘Women writing in India, 600 BC to early 20thC’, others I found through oral traditions, visual representations and popular songs. Karaikalammaiyar, who transformed herself into a dancing skeleton and signed her verse as ‘pey’ meaning ghoul, Lal Ded the Sufi who wandered naked, Mirabai who danced and sang with her lover god, spurning the prince who was her husband — these women had broken free of social mores and conventional feminine identity to celebrate their individual relationship with the metaphysical. The stories often involved bodily transformations.This aspect, of self-transformation of the body, often taking on an androgynous character, was crucial to my interest – and it was in the community of women ascetics, present and past that I found fascinating modes of inhabiting, subverting and transgressing bodily markers of gender.

Record Resist.

Record Resist.

Most meetings with women ascetics took place in situations where ascetics gather – places of pilgrimage, religious fairs like Joydev Mela Kenduli or the Kumbh Mela, or ashrams. It is now increasingly difficult for a lone woman acetic to wander alone so they tend to move in small groups, two’s and threes.

At the pilgrim centre’s, the women’s enclosure, separated from that of male ascetics is a warm, relaxed, affectionate space. A sorority of sorts, however temporary.

Becoming an insider in these spaces made me privy to the fun, the play-acting, the general hanging out and gossiping as much as to the intense moments of shaving ones head, renewing or taking vows. The woman ascetic is a performer, and these were also performative spaces – for the perception of lay people who crowd in, curious, reverent, awed – as well as others from the community. However, it is important to remember that the camera, as one recipient of this performance, came into the interaction only after spending I had spent a substantial amount of time in building a relationship with individual women.

If you could talk about the origin of moving image light boxes. It is a medium that you use often, particularly to look at the landscapes.

I am interested in durational media, and work across a spectrum, from 19th century devices to VR. I first discovered a street toy in old Delhi, a toy TV, which used an ingenious principle to create the illusion of a moving image –- just an ordinary light bulb in a cardboard box, with a cylinder of images. The heat from the bulb would make the cylinder rotate, casting images on the little plastic screen. This was similar to early pre cinematic experiments such as the Magic Lantern. I adapted and worked with the toy TV for a large installation on femininity in cinema, around the figure of Meena Kumari. When I returned to old Delhi, I found that this artisanal device had been replaced by a Chinese import – the Plasma Action TV. Now with an electronic component, these seemed emblematic of new forms of globalisation. I dismantled these, and from their rudimentary mechanisms developed the animated light box – a medium that engaged me over a number of years. It gives me a perfect interregnum between the still and the moving, eliciting a special kind of slowness, and thereby quality of attention.

When you had conceived “When the Gun Is Raised, Dialogue Stops,” it gave a voice to the women of Kashmir, who, you had stated offered an alternative to the “dominant, hegemonic” representation of the war-torn region. I was reading a statement where you said, “Kashmir is a microcosm for what is happening in many parts of the world, including the rise of the right [and] the rise of fundamentalisms.” How do you feel about the hegemonic forces in the world today?

On one hand you have the ruthless, almost desperate extraction of the last of the dwindling resources of the earth, facilitated by states and corporations who seem to forget that the profit maker is not exempt from climate change; on the other, citizens and populations are incited into violence and conflict around questions of identity and religion by both ruling regimes and fundamentalists; fear, the desire for order, the anxiety produced by the instability and precarity of daily life seeks assurance from increasingly non- democratic systems of governance.

How do you view your role as an activist-artist? Not just through art, you have also played a role through your work in citizen’s forums, for instance the Nagrik Ekta Manch that was engaged with peacekeeping activities in areas affected by the 1984 riots.

My art is itself a form of activism. Creating a space for critical contemplation on, for example, the state of the Yamuna, is a political act. I act as a “citizen artist”, sometimes simply by joining a protest or signing a petition, sometimes by working with, and bringing my skills as an artist, to an organisation like Nagrik Ekta Manch which is intervening in a crisis.I have been a part of a number of citizens movements over the last decades.

Apr 19: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05